The streets of downtown Halifax hold more than the hum of traffic and footsteps. They are layered with Mi’kmaw history and stories that predate the city by millennia.

Those voices are now being given a new platform through the Mi’kmaw SoundWalk, an interactive learning experience that turns Halifax into an open-air archive of memory, music and culture with the help of mobile technology.

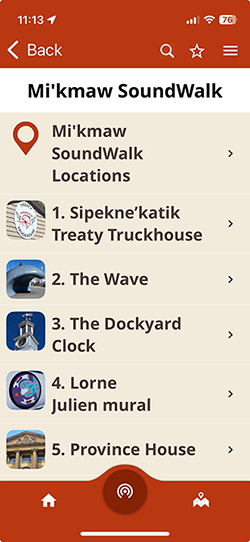

Available through the , the SoundWalk allows participants to self-guide themselves through nine historical sites across the city anytime. The app uses GPS to trigger audio and visual storytelling on a user’s device at different locations.

For Mi‚Äôkmaw people and non-Mi‚Äôkmaw people, ‚ÄúIt's a way to walk together,‚Äù says Membertou storyteller and singer, Graham Marshall, the voice behind it all.Ã˝

It's a way to walk together.

The Mi‚Äôkmaw SoundWalk came to life in collaboration with Marshall,Ã˝Dr. Jennifer Bain ‚Äî professor of musicology at Õ¯∫Ï∫⁄¡œ and a co-producer of the project ‚Äî along with Cape Breton University‚Äôs and the . Designed as a digital storytelling experience, the SoundWalk weaves together maps, photographs, audio recordings, text, and links to additional resources.

Released this year on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (Sept.30), the SoundWalk carries symbolic weight. It aims to educate, offering non-Indigenous participants a chance to engage with Mi’kmaw history at their own pace.

“There are some obvious, very important things we need to do when it comes to Truth and Reconciliation,” says Dr. Bain. “Although this doesn’t meet all those needs, having non-Mi’kmaw people, who live here in Mi'kma'ki, hear the voice of a Mi’kmaw storyteller is a good start.”

For accessibility and for those outside of Halifax, the SoundWalk can also be experienced directly through the app without visiting the sites in person.

An immersive experience

As users approach each site, the voice of Marshall is GPS-triggered. Participants pause to take in their surroundings, while he draws them into the story, asking them to “picture this land as it was before European contact.” He provides historical insight and reflection, inviting walkers to hear the ground beneath their feet in new ways.

The route begins at the Treaty Truckhouse on the Halifax’s waterfront, before moving to the Wave and Dockyard Clock. From there, participants are guided to the Lorne Julien mural in Granville Park, Province House, and Grande Parade, before continuing along Barrington to Spring Garden, with final stops at St. Mary’s Basilica, Grafton Park, and the Public Gardens.

The route begins at the Treaty Truckhouse on the Halifax’s waterfront, before moving to the Wave and Dockyard Clock. From there, participants are guided to the Lorne Julien mural in Granville Park, Province House, and Grande Parade, before continuing along Barrington to Spring Garden, with final stops at St. Mary’s Basilica, Grafton Park, and the Public Gardens.

Each location carries its own resonance. At the Basilica site, singer Walter Denny Jr. shares a Mi’kmaw Catholic chant for St. Anne.

The Wave, an iconic monument on the Halifax Waterfront and second site of the SoundWalk, is repositioned by Marshall as a symbol of the Mi’kmaw connection to water, vital for food, travel, and protection.

In the audio recording he says, “In the land of the Mi’kmaw, we are surrounded by water. The water was our highways. When you see the highways on which vehicles are driving on, they are parallel to old Mi’kmaw rivers that were utilized before that. That was our way of protecting our territory. But also in peace and friendship.”

For Ostashewski, a multimedia approach fit the project well. “When you do things in different formats simultaneously, you are connecting with different audiences who connect through different channels,” she says. “It allows us to share knowledge and information to a broader audience.”

A new lens on Halifax landmarks

Halifax was a deliberate choice, not only as a city with deep Mi’kmaw roots, but also as one of Canada’s most vibrant tourism hubs. “A lot of foreign visitors to Canada, when they travel here, one of the things they say they want to do is experience Indigenous culture,” says Dr. Bain. The creators hope the project can help expand the development of Mi’kmaw business opportunities.

For scholars and students, the project is both a teaching tool and a new lens on the city. Dr. Ajay Parasram, a professor of International Development at Dal, is excited about the learning, imagining, and reconciling to come, having already assigned the SoundWalk to students in his Halifax and the World course.

“Everybody has this relatively static and simplistic understanding of Canada from the outside and even from other regions of Canada,” Dr. Parasram says. “Understanding Halifax as a global city, an imperial city for hundreds of years, I think is going to be transformative for people who don't know that much about Halifax, but also those who think they know a lot about Halifax.”

This is about Mi’kmaw people telling stories about Mi’kmaw places in Mi’kmaw voices.

Halifax’s long-closed Memorial Library on Spring Garden Road, built atop a former cemetery, marks the eighth site on the SoundWalk. It also serves as the project's installation site for the , Halifax’s immersive arts celebration. This year, the festival's theme is Ground, offering a timely opportunity to reflect on those who were here first.

“This is about Mi’kmaw people telling stories about Mi’kmaw places and experiences in Mi’kmaw voices,” Ostashewski says.

Throughout Mi’kmaw History Month this October, and everyday thereafter, each step — whether along the waterfront, through a cemetery, or in the Public Gardens — echoes with the same reminder: we are walking on Mi’kmaw ground.